March’s Tiny Movers: London’s Invertebrates Awaken

As March warms, London’s hidden world of invertebrates comes alive. From earthworms surfacing to slugs and snails emerging from hibernation, the city’s smallest residents are on the move. Discover the fascinating, and sometimes quirky, behaviors of woodlice, centipedes, and millipedes as they begin their springtime activities. Did you know woodlice once cured “bad lovers” or that millipedes can live up to seven years? Join us on 28 March to uncover the secrets of London’s invertebrate world. Don’t miss this glimpse into the tiny lives shaping our ecosystem!

Many invertebrates are now on the move again and there is considerable amorous activity among them. Earthworms, slugs and snails are all pairing, the former even occasionally being seen on the surface. Cold weather generally drives many of them either deeper into the ground or further down the crevice which they had chosen to over-winter. Now higher temperatures begin to draw them all out. Once awake, egg-laying soon commences for many invertebrates. There are eighty land snails, twenty-three slugs, forty-six woodlice, forty-four different centipedes and fifty millipedes in Britain, so identification can be somewhat troublesome. Many of these creatures shun the light and are mainly nocturnal, resulting in most of us only encountering them when we lift a stone. Woodlice are very sensitive to humidity and cannot breathe in dry conditions.

Oniscus asellus and Porcellio scaber are particularly common. The woodlouse that rolls up into a pill, Armadillidium vulgare, is always the most popular. In the past, it was eaten as a cure for ‘bad lovers’. Like so many other invertebrates, woodlice have an unpleasant side to their nature. In this case they eat their own faeces, and even each other occasionally. They are at their most vulnerable after they moult as their mouthparts are at first too soft to defend themselves.

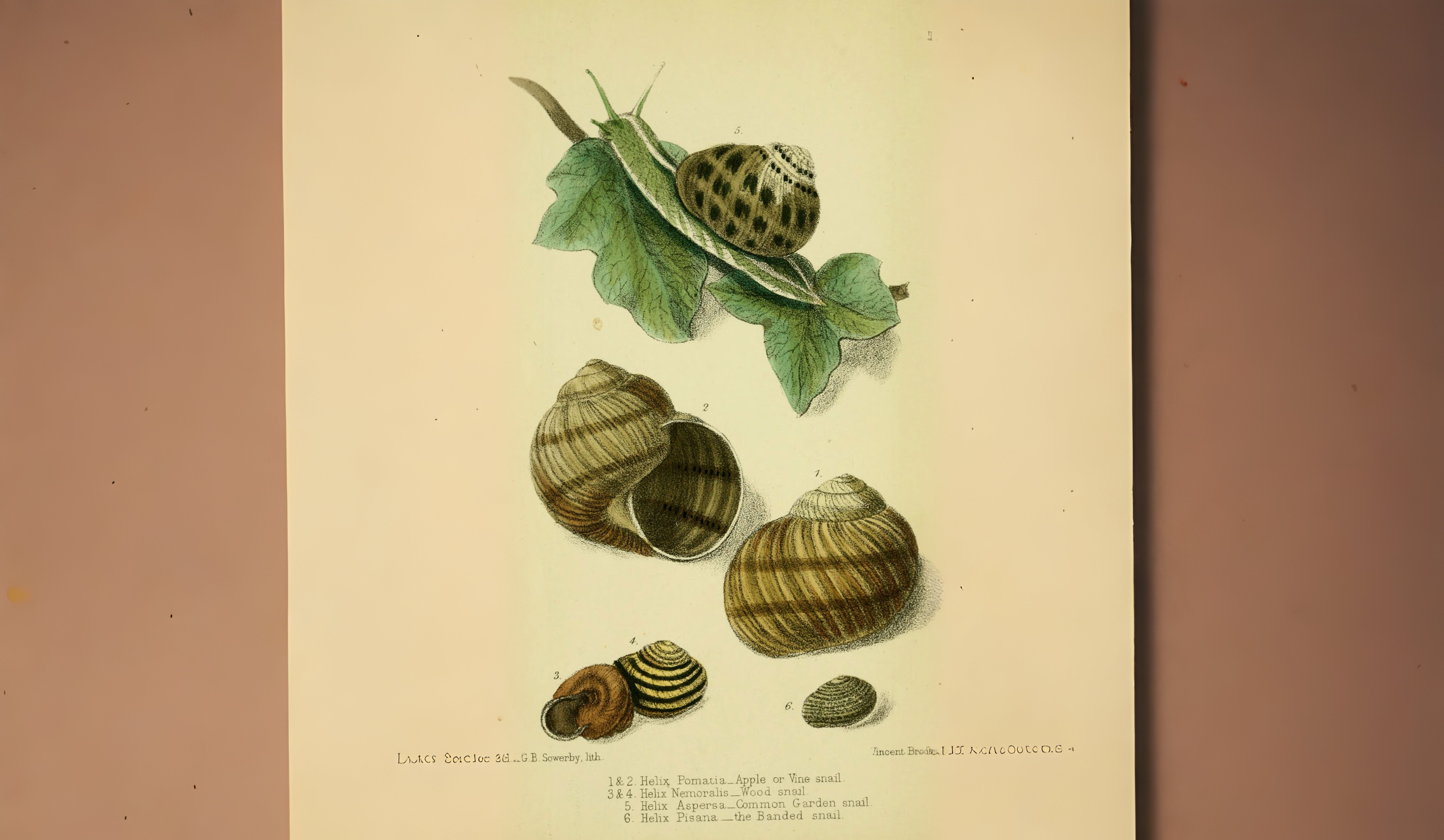

Rain brings out slugs and snails, especially if it is warm rain. Evidence of their presence is usually first noticed when we see half-eaten leaves. Slugs are thoroughly nocturnal and again not too particular what they eat. Alive or dead seems to make little difference. Their eggs may be hatching this month and, when small, they also can be difficult to identify. Even when adult, they can have a number of different colours and their mucus is often also pigmented. Garden snails do not travel as far as slugs at night, but with fourteen thousand ‘teeth’, a single snail can do considerable damage to any fresh leaves it encounters. On the North Downs, the prized Roman snail Helix pomatia is also now on the move. Like many other snails, it formed a chalky membrane across the entrance to its shell to avoid the rigours of winter. This is now broken open, marking the end of its hibernation.

The first centipede seen is usually the common orange-red Lithobius forficatus, glimpsed as it scuttles away when we disturb a stone. As it runs, it may only have three legs actually touching the ground at any one time. Many centipedes have either no eyes or poor ones, relying much more on vibration to seek out their prey. Some have mouthparts capable of injecting a mild venom although his usually goes unnoticed if humans are bitten.

Among the millipedes, the black snake millipede Tachypodoiulus niger is one of the species we see most often. It curls up into flattened coils when disturbed and produces an unpleasant fluid. Some can be surprisingly long-lived, reaching the grand old age of seven years. In the past people opened their windows on windy days in March in the mistaken belief this was the way to get rid of fleas. Depending on the way the wind was blowing neighbours would close theirs.