This month, London’s waterways and woodlands burst into life with dazzling flowers—from explosive Himalayan balsams to deadly hemlock water dropwort. But that’s just the beginning. Return on 10 July to uncover rare bog-dwelling carnivorous plants, floating water soldiers, and the mysterious Martagon lily lurking in ancient woods. Don’t miss the secrets of London’s wildest blooms!

The balsams are a particularly attractive group. It is the Himalayan balsam Impatiens glandulifera that gets the most attention. This is mainly because it is an alien which aggressively takes over some riverbanks to the exclusion of everything else and also partly because of its fruits. When fully ripe, these dramatically explode when touched. Orange balsam I. capensis is one of our few orange flowers. It can be found along some portions of the river Lea.

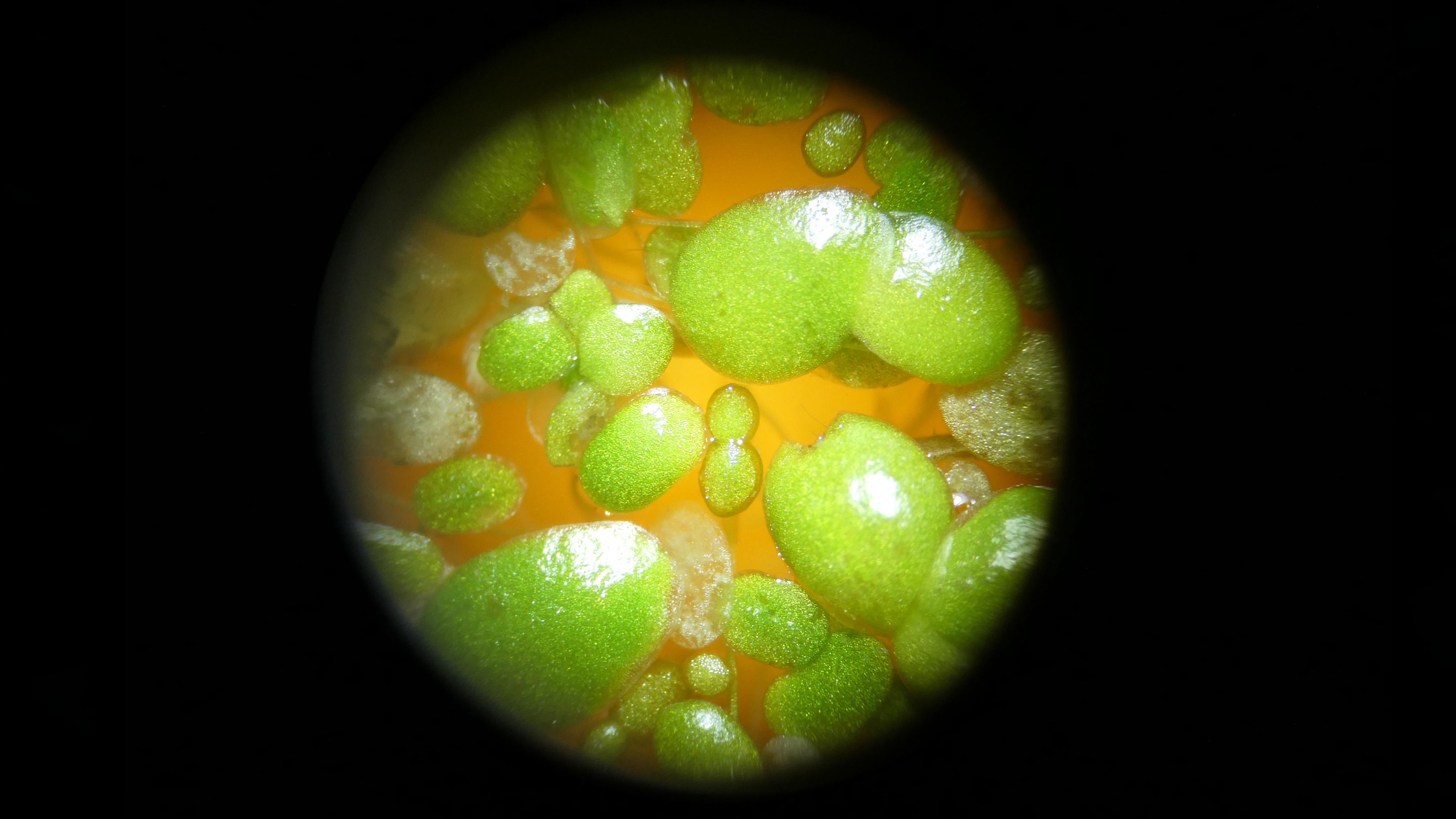

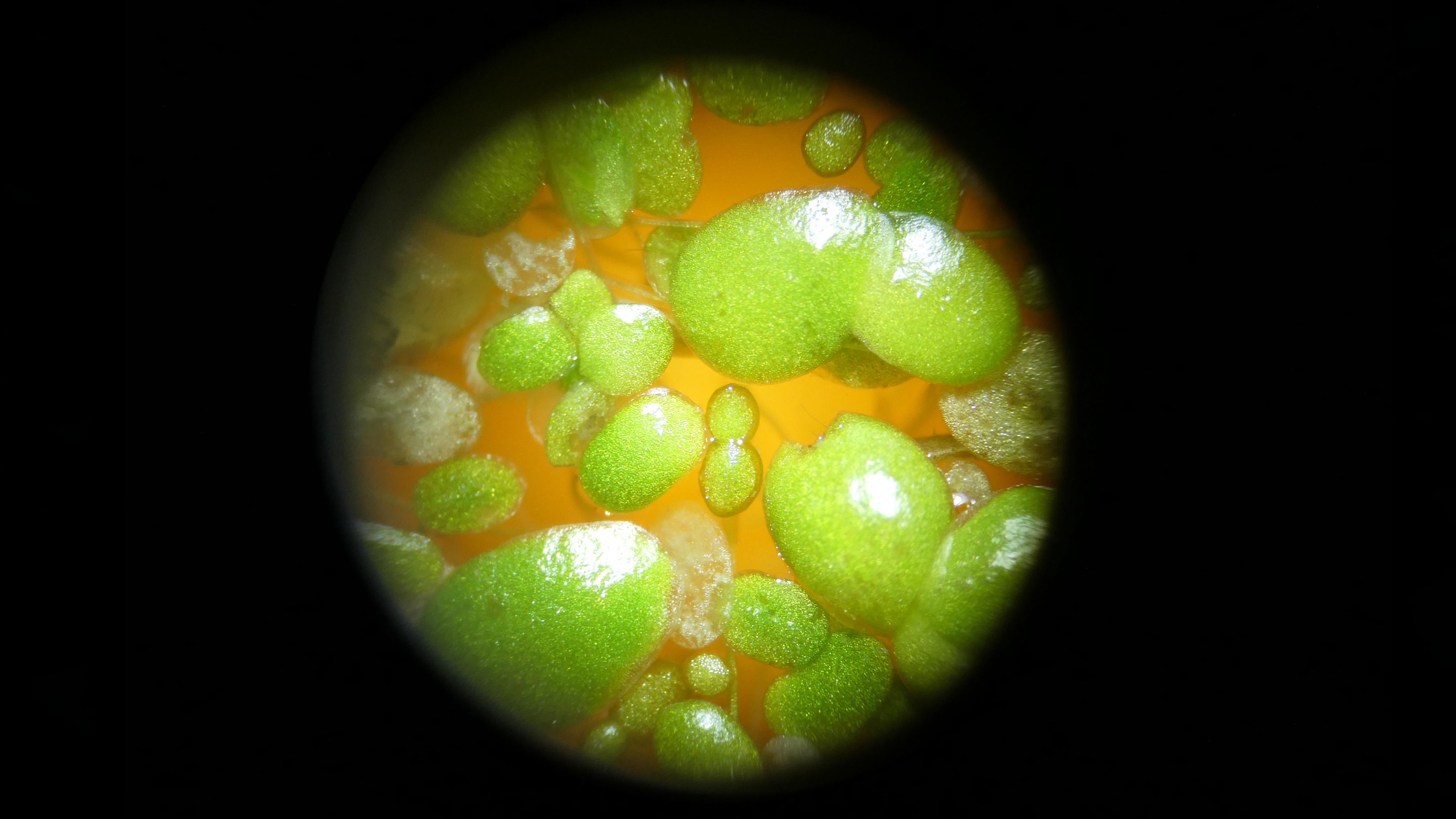

The showiest of our waterside plants are probably the monkey flowers Mimulus spp. There are three in London, mainly seen in water gardens. Occasionally, they do occur in the wild, especially along parts of the rivers Colne and Derwent. The monkey flower M. guttatus is the most likely to be seen with its custard yellow flowers, Blood-drop emlets M. luteus is more attractive on account of the red splashes on its yellow flowers.

A pleasant and easy way to become acquainted with waterside plants this month is just to walk along the banks of the River Wandle as it meanders through Beddington Park and then Morden Hall Park. Including any ponds and nearby marsh you can find up to seventy different species of waterside and submerged plants in both places. These include five different water cresses (Rorippa spp.), three different duckweeds, stonewort, monkey flower, brooklime and royal fern in Beddington Park and five different sedges, two bur-reeds, water fern and skunk cabbage in Morden Hall Park.

Butterwort employs a similar strategy but in this case there are no hairs on its fleshy leaves. However, they are sticky and roll up to engulf any insect that lands on them. Epsom forest is still a place to look for both these plants as well as one of the most unusual of all insectivorous plants, Bladderwort Utricularia vulgaris. Its small, canary yellow flowers set on thin stems coming out of water are the first thing you notice. These give no clue to what is happening below the water surface. There is a mass of floating filaments with small, clear bladders attached to them.

One of the most atmospheric bog habitats to visit is on Keston Common. This is where Charles Darwin is believed to have studied the plants before writing his book on the subject. Although any insectivorous plants may now be hard to find other attractive bog plants such as Bog Asphodel and Cotton grass may still be seen. Among the seven sphagnum mosses recorded there are the brightly coloured red species Sphagnum capillifolium ssp. Rubellum and S. magellanicum.

The violets and anemones of spring are now long gone, bluebells are running to seed and dog’s mercury will soon disappear altogether underground. At first glance most London woods are covered in bramble, ivy and nettles. In the less well-trodden woods it is easy enough to find herb bennet, enchanter’s nightshade, goldilocks, wood sage and foxgloves. In older more ancient woods, less common species such as sanicle, wild strawberry and common cow wheat Melampyrum pratense are more likely to be seen. Cow wheat is one of the most attractive woodland flowers of the month. The damper woods around Bromley are good places to see it. It has groups of two pure citrus yellow flowers, both pointing in the same direction. It is unusual in woodland, being an annual and also in the way in which it lives by parasitizing nearby plants, taking both water and minerals from them. In the past it was eaten by pregnant mothers to ensure they had a boy. Cows were thought to favour it, resulting in brighter yellow butter. The wheat connection came from the seeds of other cow wheats, which contaminated crops resulting in bitter tasting bread.

Other attractive species that get noticed at this time of year are Burnet saxifrage Pimpinella saxifraga, Water avens Geum rivale, Betony Stachys offinalis, and one or two bellflowers Campanula spp.