July transforms London’s meadows, riverbanks, and forgotten wastelands into a living tapestry of wildflowers—where knapweeds stand like purple crowns and vervain whispers ancient Roman secrets. But the real magic lies in the overlooked rushes: once used for thatching, fortune-telling, and even lighting Tudor homes. From Devil’s-bit scabious to spiral-stemmed oddities, discover the unsung heroes of the city’s grasslands.

Return on 05 July to unravel the stories woven into London’s summer flora!

July is another astonishingly rich month for wild flowers. Many spring flowers are now just a memory and others, which had their main flowering period earlier, are developing fruits with the occasional flower. All these are now joined by the late-flowering species. One of the most attractive habitats to look for flowers this month is along the edges of rivers or lakes, closely followed by meadows and downland. Hedgerows, woodland and waste areas are also good places. The latter may be less attractive than other habitats but often harbours rare aliens and hybrids. Certain plant groups such as thistles, mallows, mulleins, hempnettles and willowherbs all seem to belong to this month. The same is true of various representatives among the composites, clovers and vetches.

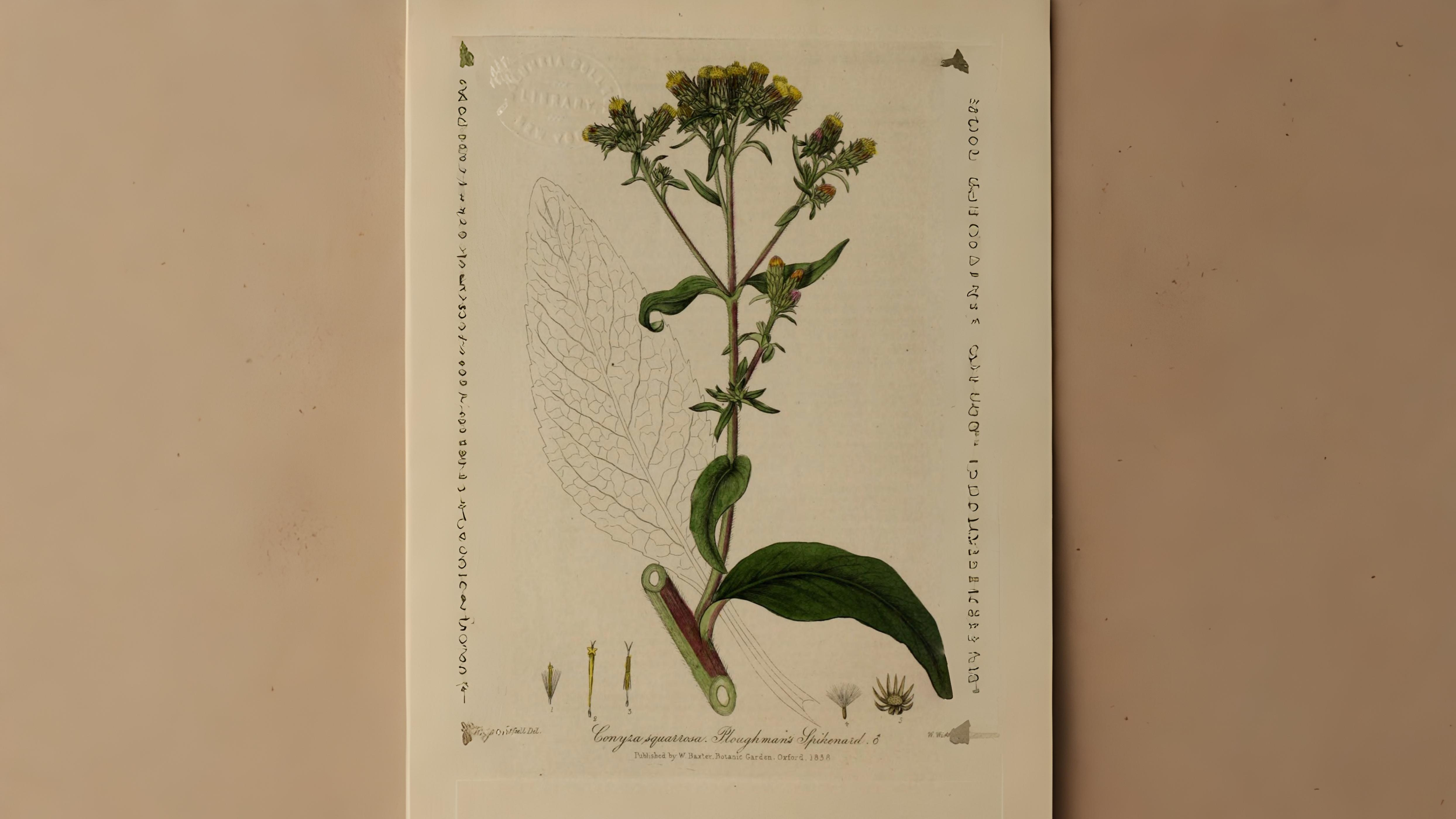

Downland often provides the most pleasant plant hunting at this time of year. It is worth looking for rarer species such as burnet saxifrage, field and crow garlic, sainfoin, yellow rattle, common calamint, Dyer’s greenweed and ploughman’s spikenard. The flowers of dyer’s greenweed yield a yellow dye which, when mixed with woad, provided a much more useful green dye. Ploughman’s spikenard got its unusual name from being the poor man’s equivalent of true spikenard which was much sought after for its scent.

The dried roots of both used to be hung up in cottages to sweeten the air and kill fleas. The less frequented downs between Merstham and Kemsing are good places to look for these flowers as well as the more popular Farthing Down. Wherever the ground is excessively grazed by rabbits it is worth looking for hound’s-tongue. In this case the English name refers to the shape and texture of its leaves.

Other plants more commonly seen are wild basil, knapweeds, rockrose and various types of scabious. The largest and most impressive of the scabious species is the Devil’s bit scabious Succisa pratensis. This grows up to one metre in height with rounded mauve rather than blue flowers. The field scabious Knautia arvensis and small scabious Scabiosa columbaria both have blue flowers but can be separated more easily by their flower shapes.

Those of the field scabious tend to be flatter than the small scabious whose flowers are slightly more dome-shaped. Both grow together on Kemsing Down. Knapweeds, which look like small soft thistles, also stand out now. Common knapweed Centaurea nigra is the most common, identified by its small flowerheads and mostly undivided leaves. The rarer saw-wort Serratula tinctoria looks similar but has highly toothed leaves as its name suggests. It still hangs on in undisturbed grassland. The most handsome of the group is the much larger and impressive greater knapweed Centaurea scabiosa.

This also has divided leaves which are not toothed but softly lobed. A similar-looking garden flower is the cornflower Centaurea cyanus which is easily distinguished by its piercing blue rather than the typical purple of knapweed flowers.

Besides the paths in the areas of downland mentioned, vervain Verbena officinalis is quite common. This is another plant with a rich folklore. The Romans called it herba sacra and on their feast of Verbenalia they laid it on the altars on which they were to carry out animal sacrifices. In Britain the druids included it in their lustral water which was used much as holy water is used in churches today. Vervain was also thought to help people make accurate prophecies and so was popular with fortune tellers. Christians believed it was used to help staunch the blood from Christ’s wounds. Being such a powerful herb, it was an obvious choice to put around children’s necks to protect them from any illness. Other less visited patches of excellent downland where the number of different plants per square metre can approach forty or more are Quarry Hangers, Saltbox hill and parts of Happy Valley.

Rushes, Clubrushes, Spike Rushes and Bulrushes

Many of the plants we call rushes belong to several other different genera and a few are actually sedges. The most recognisable are those dense clumps of boldly upright narrow tubular leaves with small flower clusters on the sides of similar-looking stems that indicate the land is probably poorly drained and difficult to farm. However, most rushes have their small, insignificant brown or black flowers set on quite rigid, often jointed, branches at the end of their stems. As they are all wind pollinated they have no need for petals and in many cases even their leaves are reduced just to scaly sheaths at the base of their stems. All in all they are easily missed.

In fact identifying them in the field is not for the faint-hearted although their English names can often give a clue. It is always worth noting their size, colour and with a lens their flower and fruit. Occasionally you may even need to split a leaf to see if it has any compartments of pith inside. July is generally a good time to look at them as most are now either in flower or fruit. Although very much associated with marshy ground and wet heaths, they are also found at the edges of woods, fens, bogs and even beside canals and in gardens. Good places to look for them are Wimbledon Common, which has seven of our more common species, Perivale Wood which has five species and Islip Manor which has four.

Economically they have always been regarded as useless as many are of poor nutritional value and livestock often refuse to eat them. However, other uses have been found such as being used for thatching, making mats, chair seats and even ropes. There were even rush fairs in the past where bundles were sold to be used as strewing herbs before carpets were created. One of Cardinal Wolsey’s so called extravagances which brought his downfall was that he changed the strewing herbs in his palaces once a week. They were laid on the floor and often scattered with flower petals. Another important use was the making of rush lights by the poor who couldn’t afford candles. They would cut the leaves then partially strip them before laying them in any old rendered fat left in the kitchen. Once left to dry they were then capable of burning for as long as five hours, which must have been a godsend for many a poor Londoner in the depths of winter.

The most common clumps of rushes we notice in fields tend to be either soft rushes Juncus effuses, hard rushes J. inflexus or the compact rush J. conglomeratus. All have their flowers at the sides of their stems. If the stem is rolled between your fingers and thumb and has no ridges it is likely to be a soft rush. If the leaves of the tussock are rather stiff and slightly bluish green it could well be a hard rush and if the flowers are compacted in a ball rather than falling loosely then it is likely to be a compact rush. Another really common much smaller rush which is often the first you see is the toadrush J. bufonius. This is ubiquitous, even occurring on paths and in gardens. It is slightly unusual for a rush producing its repeatedly forked flower branches from quite low down on its stems which only reach ten centimetres in height.

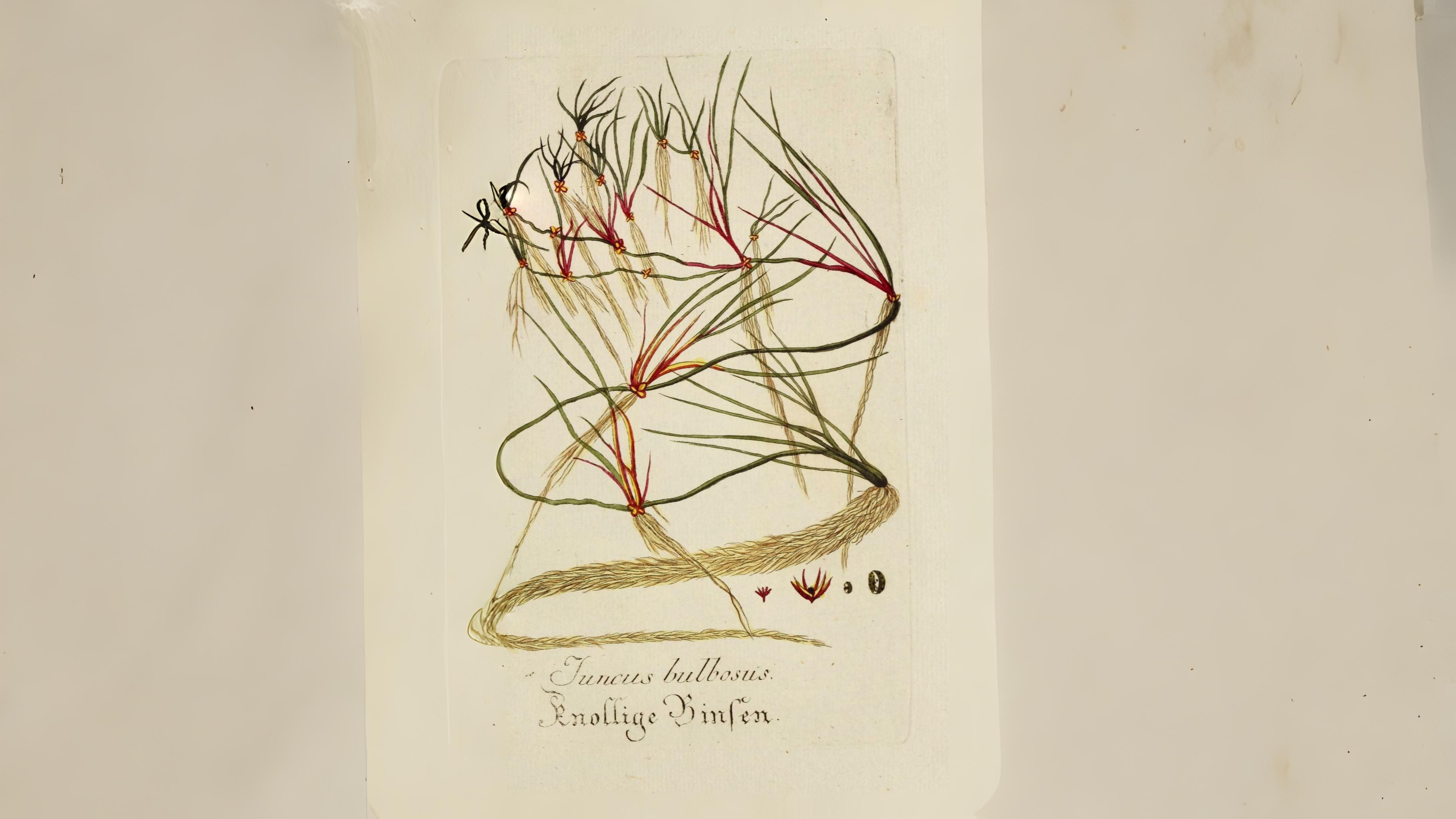

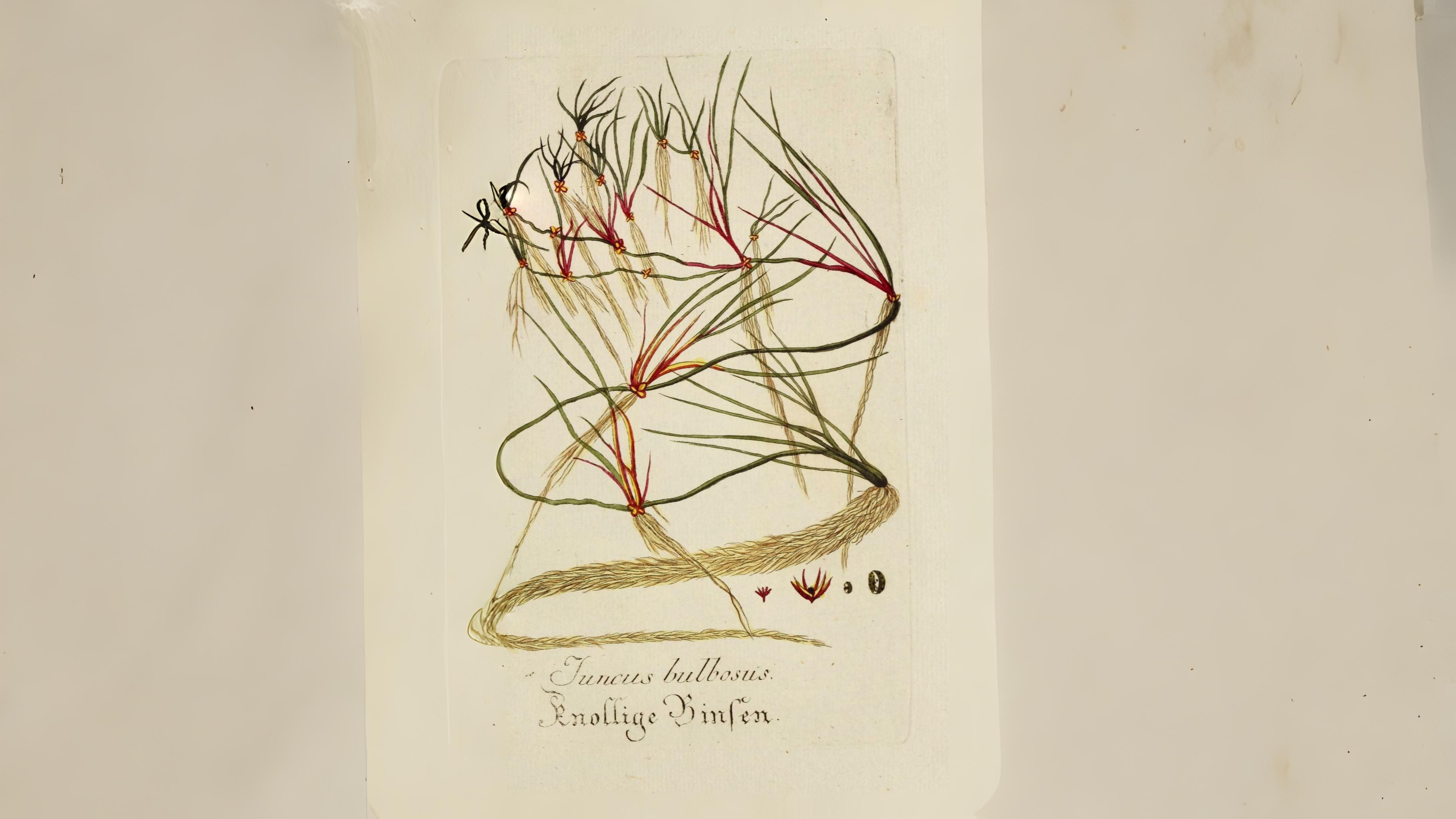

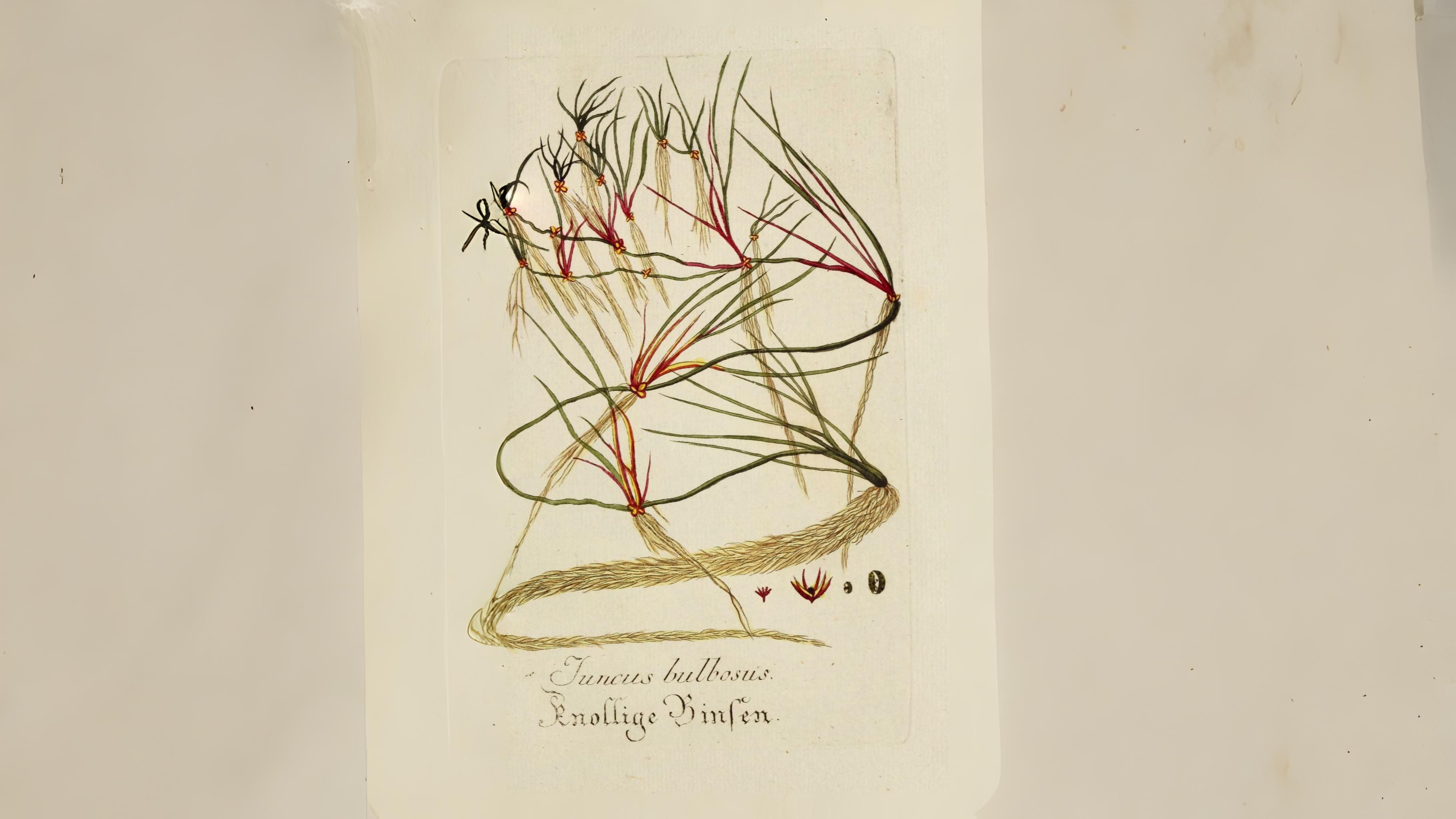

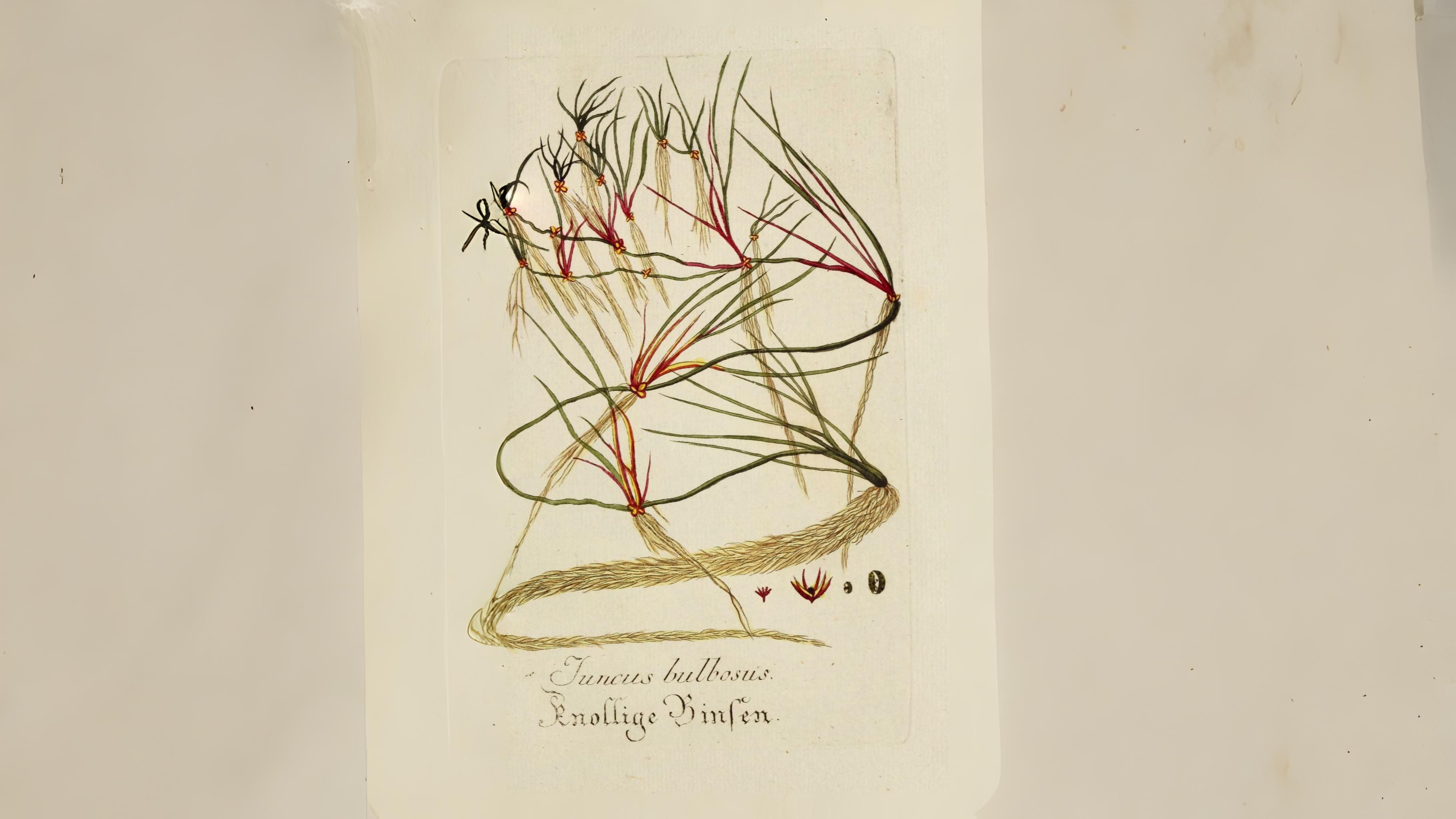

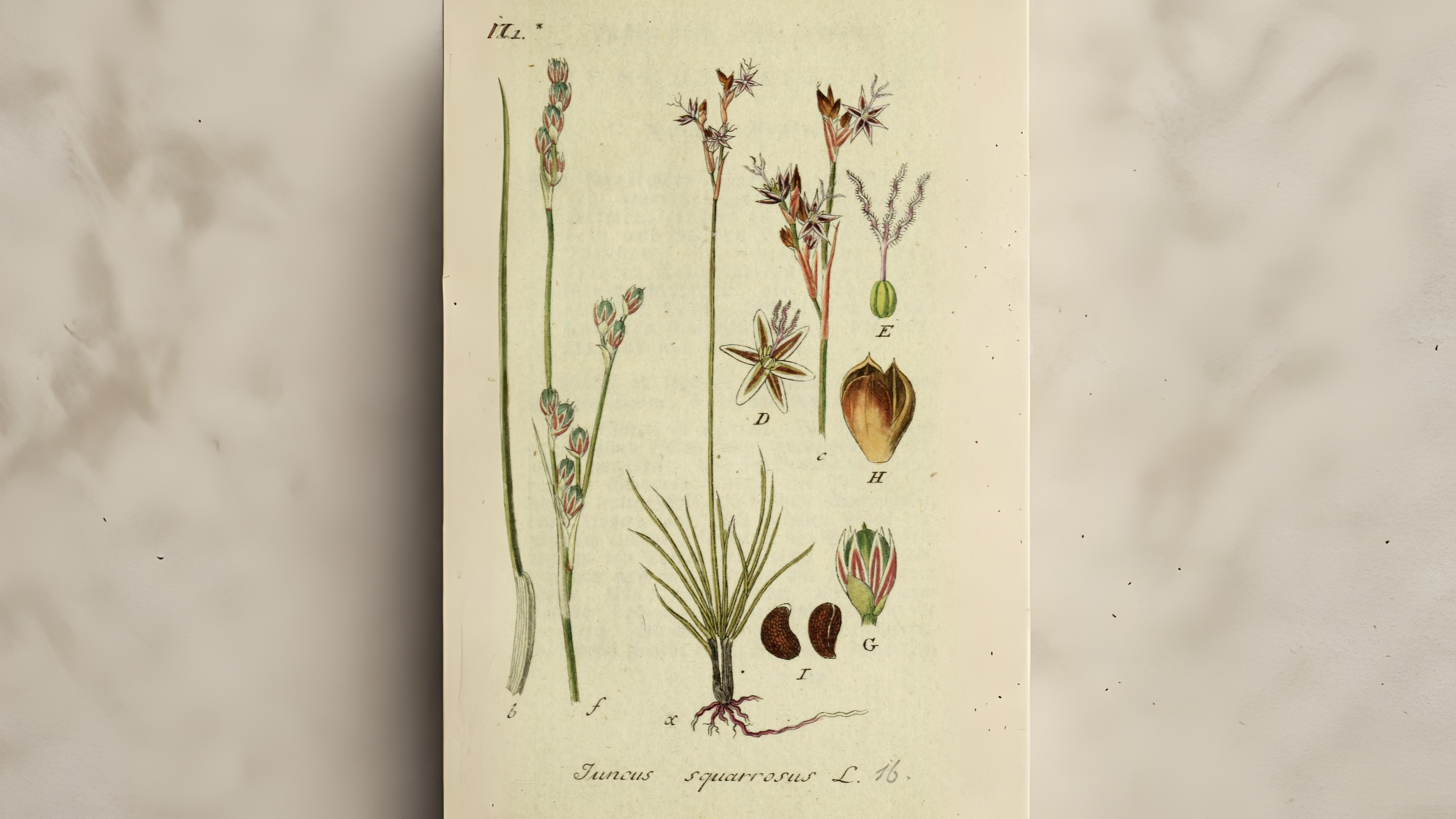

Then there are the less commonly encountered rushes with flowers at the end of their stems such as the heath, jointed, bulbous, sharp-flowered, blunt-flowered and round-fruited rush. The heath rush J. squarrosus as you might expect is found on heaths and has basal tufts not unlike a chimney sweep’s brush. It also has pale margins to its flowers, sometimes giving it a silvery look. The jointed rush J. articulatus can sometimes cover large areas. It has a habit of lying down then curving upwards to produce its flowers and egg-shaped fruits.

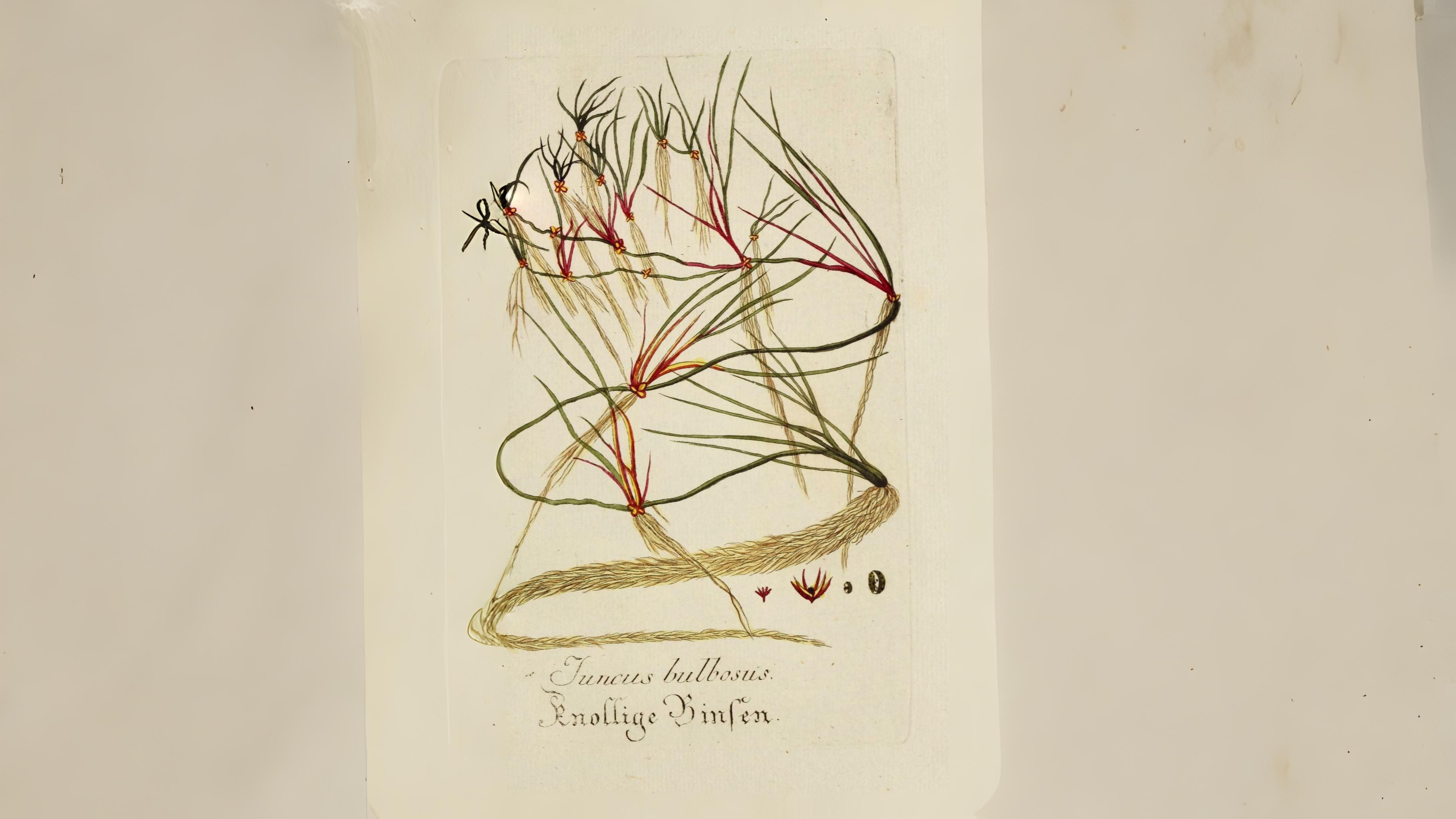

The bulbous rush J. bulbosus is often first noticed half submerged in water on boggy heaths. The sharp-fruited rush J. acutiflorus is similar-looking but with distinctly pointed fruits. If you were to strip a leaf you would find longitudinal compartments of pith. The blunt-flowered rush J. subnodulosus again is similar but with much blunter tips to its fruits and both longitudinal and cross compartments inside its stems. Because of these compartments both these rushes have leaves that feel jointed along their length. The found-fruited rush J. compressus with its round fruit is rare in our area and only likely to be encountered beside the non-tidal parts of the river Thames.

Any rushes seen in saltmarshes have a good chance of being the saltmarsh rush J. gerardii and along canal tow paths the slender rush J. tenuis can be found due to its sticky seeds getting attached to the shoes of canal boat owners.

Our other “rushes” are quite varied in appearance as they are often not true rushes at all. They also are difficult to identify, so much so they have even confused artists. Moses, who is supposed to have been found in bulrushes, is usually found in paintings in reeds or reedmace and Sir Belvedere, who is said to have thrown Excalibur into the lake from a bed of bulrushes, is often depicted standing in irises.

The true bulrush Schoenoplectus lacustris is impressive enough in its own right. It regularly reaches two metres in height and has attractive clusters of round, slightly pointed reddish-brown flowers, so much so it is often planted as an ornamental around lakes. This group of rushes are often called club rushes. Other clubrushes that might be seen are the bristle club rush Scirpus setaceus in Perivale Wood, the sea club rush S. maritimus on Erith marshes and the floating club rush Eleogiton fluitans floating in ditches.

Spike rushes are altogether smaller and just like stems with arrow-tip flowerheads. The common spike rush Eleocharis palustris can be seen growing on Rainham marshes. Lastly, it is worth mentioning the Japanese corkscrew rush J. effuses spiralis. This is a novelty cultivar of our native soft rush. It has taken the natural tendency of some rushes to twist their stems to the limit where they all just look like helical spirals.