As July unfolds, London’s birdlife shifts from dawn choruses to fleeting outbursts—blackbirds, wrens, and even pheasants break the summer silence. But where have the nightingales gone? And why do swifts scream louder in stormy skies? Discover the hidden rhythms of the city’s avian world, from vanishing corn buntings to murmuring flocks of starlings and swallows.

Return on 02 July to unravel the mysteries of midsummer birdsong!

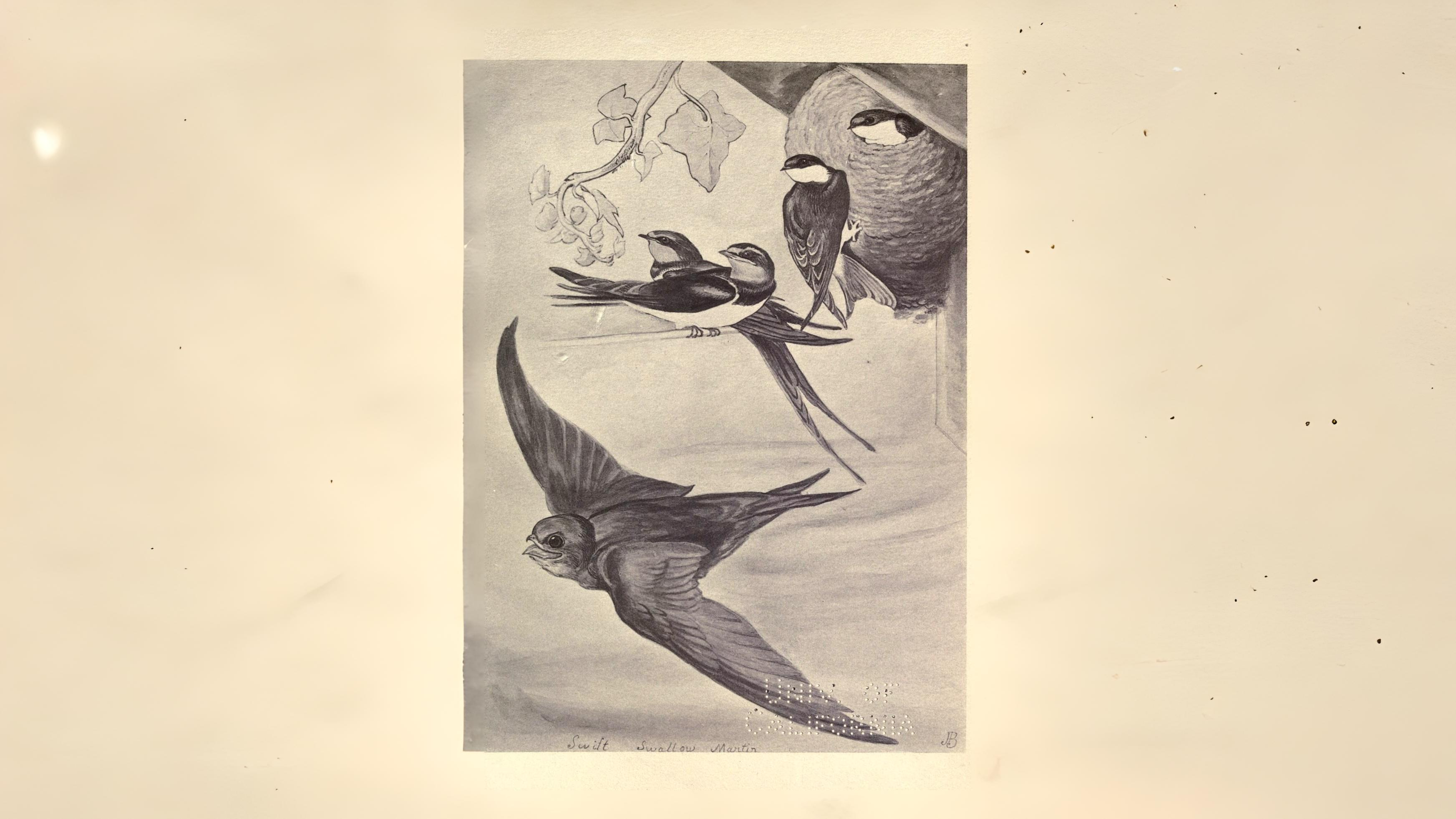

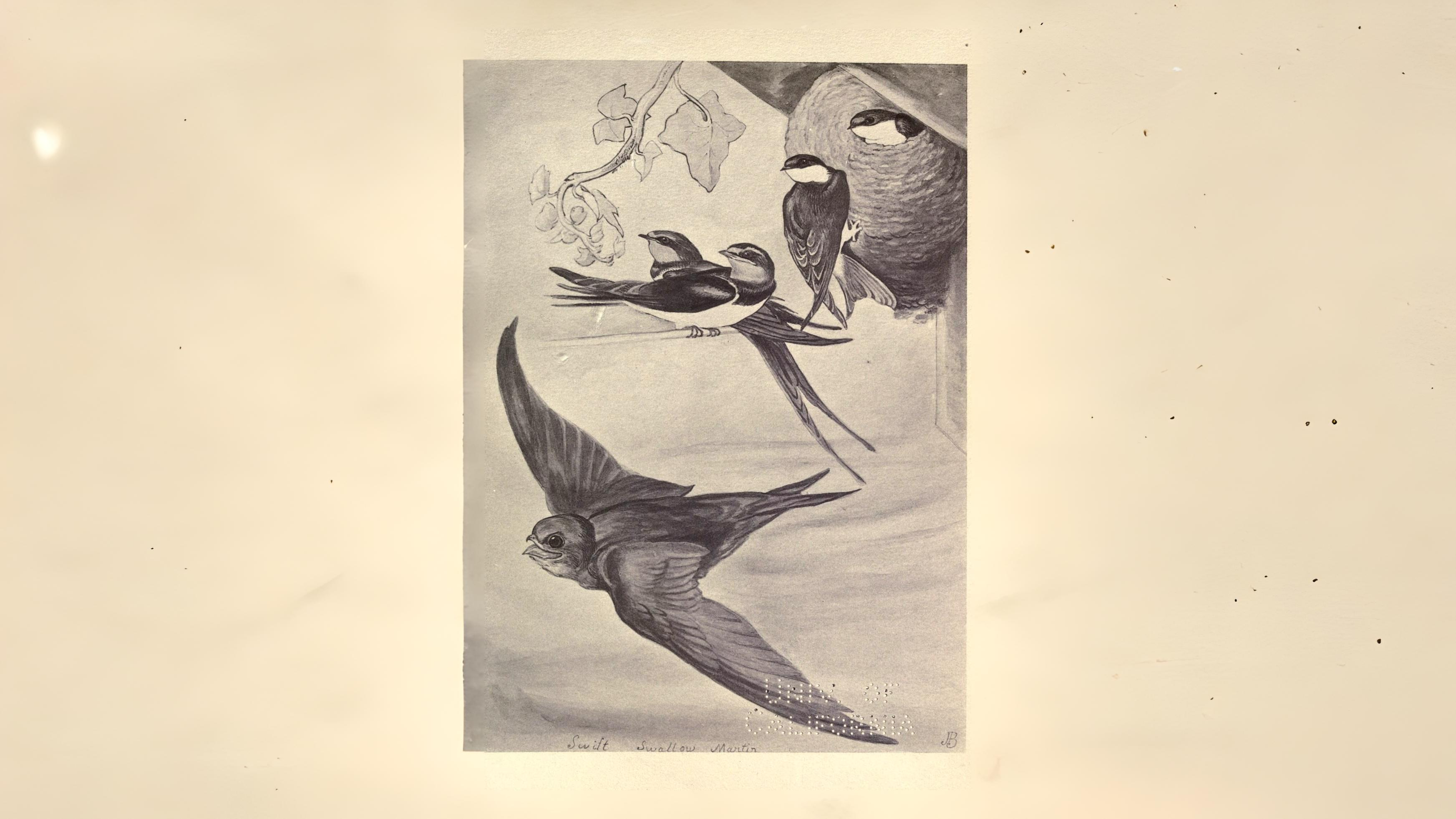

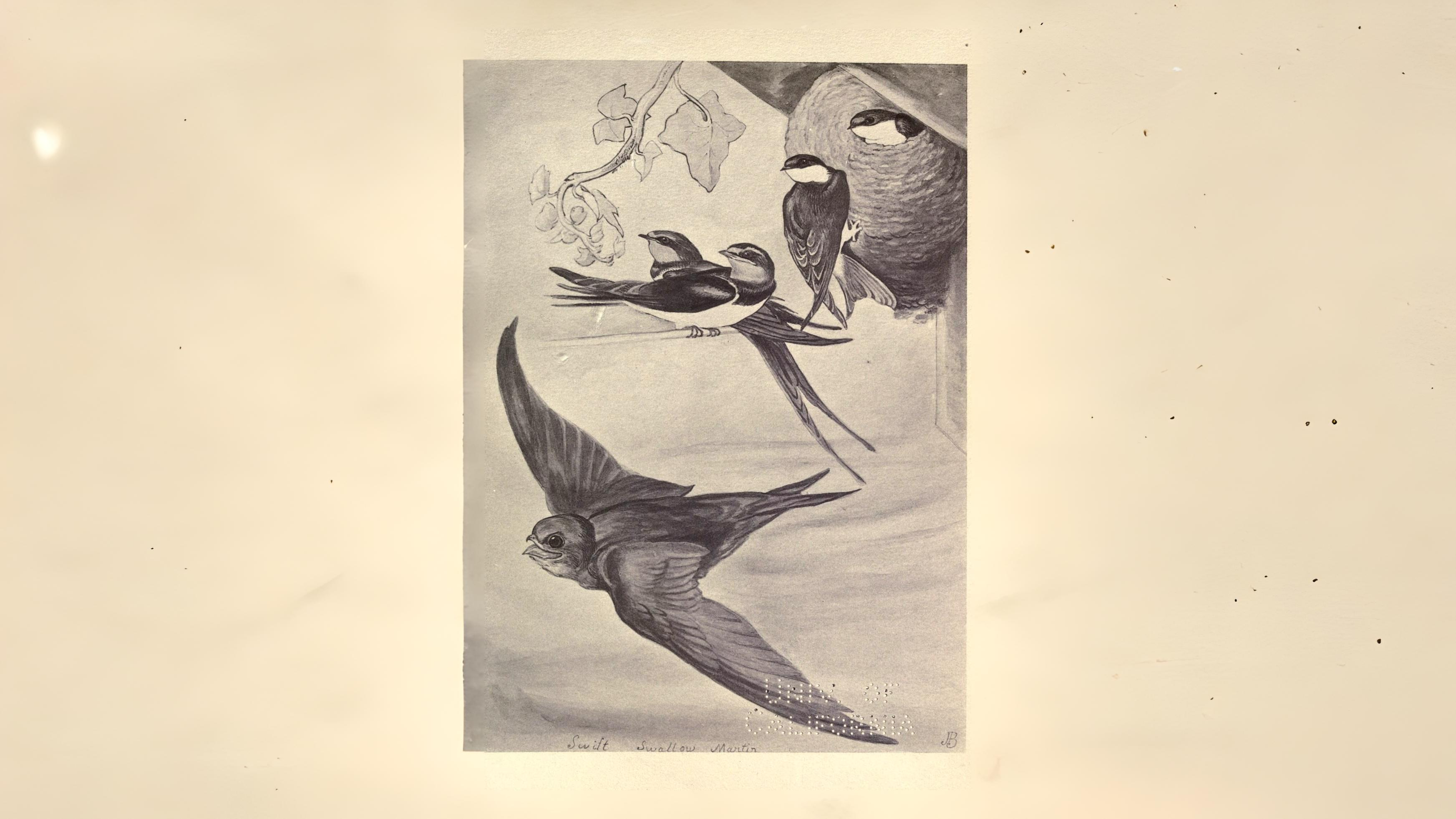

At the beginning of July there is still a variety of birds that can be heard, although the sounds are usually just short outbursts rather than any true song. In gardens, blackbirds, song thrushes, wrens, hedge sparrows, goldfinches and greenfinches are all possibilities. House martins nesting under eaves may be still quite vocal with their young well into the night. In contrast, families of swifts are starting to scream as they chase each other, particularly during thundery weather.

Woods tend to be silent but blackcap, chiffchaff, garden warbler, green woodpecker and great spotted woodpecker are all known to break the silence. If pheasants are disturbed their crowing can be heard for some distance. They were even known to reply to distant cannon fire during the First World War. In more grassy areas there is still the possibility of hearing skylark, meadow pipit, lapwing and linnet. If there is some scrub the list can get bigger with whitethroat, stonechat and whinchat joining in.

Although unlikely to be heard this is the best time to listen for the famous ‘jangling keys’ call of the corn bunting which is usually delivered from a fence post in a traditional farming landscape. Such landscapes around London are disappearing fast accounting for its sad decline. It has a song which divides most listeners - to some it sounds like a harpsichord and to others like breaking glass. The bird itself, when it sings, looks solid, streaky and slightly ‘puffed up’. The word ‘bunting’ can mean plump, hence the nursery rhyme ‘Bye Bye baby bunting’. It seems to have always preferred east London and places like the Ingrebourne valley, where there is still a traditional agricultural landscape making it a good place to look.

Wetter areas have their own compliment of late singers e.g. sedge and reed warblers, reed bunting and perhaps even the occasional snipe. Birds which ignore the general trend and can be heard regularly, even continuously throughout the whole month, are jackdaws, wood pigeons, stock doves, yellowhammers and of course the constant cooing of London’s feral pigeons and raucous parakeets. Towards the end of the month there is a marked tailing off of nearly all these sounds. Birds which may have been noticeable by their constant silence are tits, starlings, mistle thrushes, tree creepers, nuthatches, pied wagtails and nightingales. By the end of the month bird song is probably at its lowest ebb of the whole year.

Species which nested early may well now be seen in flocks. This is also a month to look for family groups. Handsome families of mistle thrushes, usually making little or no noise, may be seen in places such as Osterly Park. More rarely these families join into flocks and pass through suburban gardens. Other birds flocking this month include crows, chaffinches, rooks, lapwings, redshanks, linnets and sparrows. Goldfinches and tits are still in family groups. Starlings are not spending as much time in families, with older birds now preferring to congregate with other adults. Towards the end of the month swallows and martins form larger and larger groups, sometimes descending into reedbeds in order to roost together.

Swifts are also building up their numbers; they get noticed in good breeding years when screaming parties fly over, not far above head height. The loudest in such parties was thought to be the leader marshalling the rest for the long journey south. Now it is believed just to be a parent being pursued by recently fledged offspring. Flocks of black headed gulls returning from their remote breeding areas are also starting to be seen again.