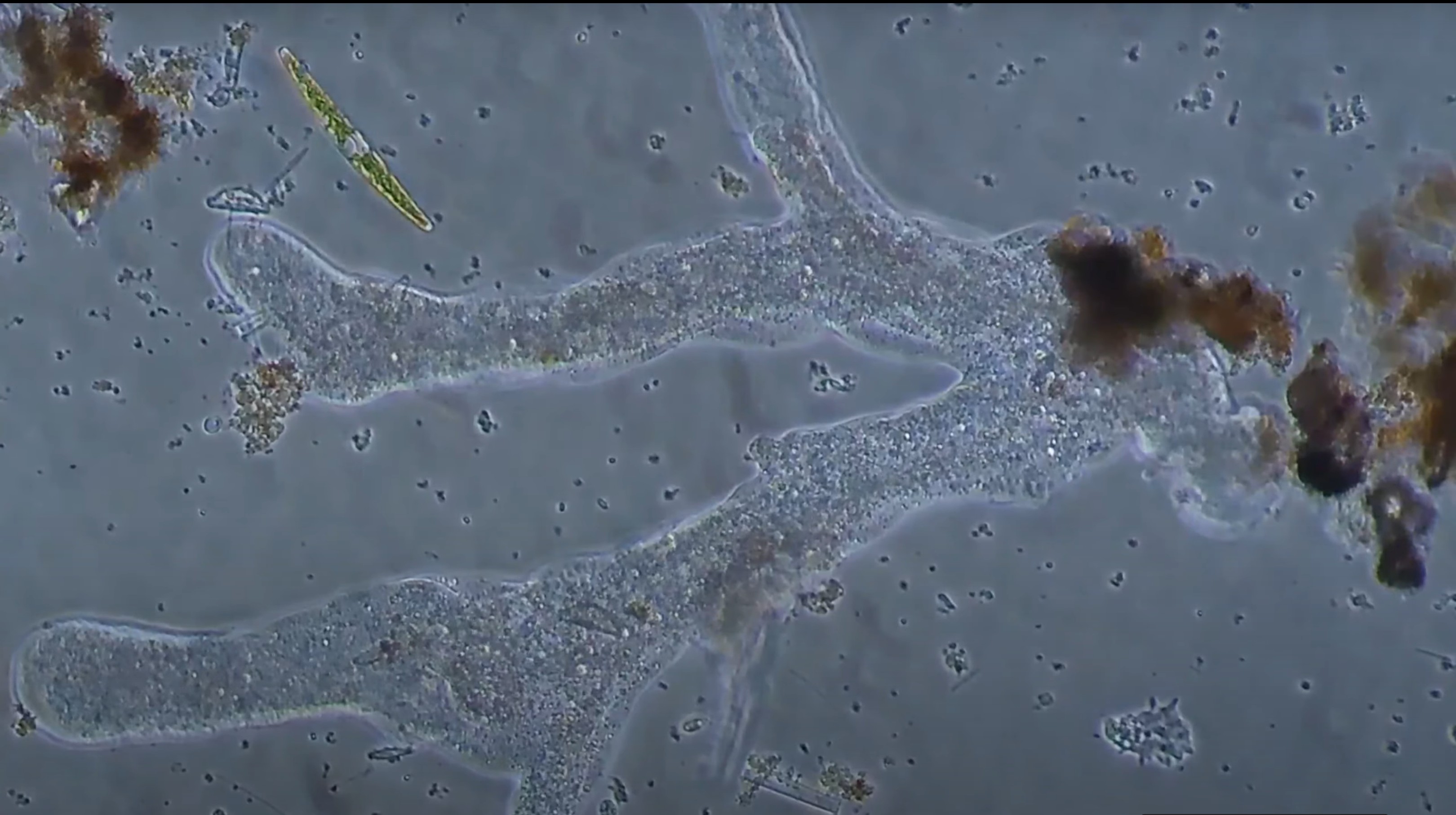

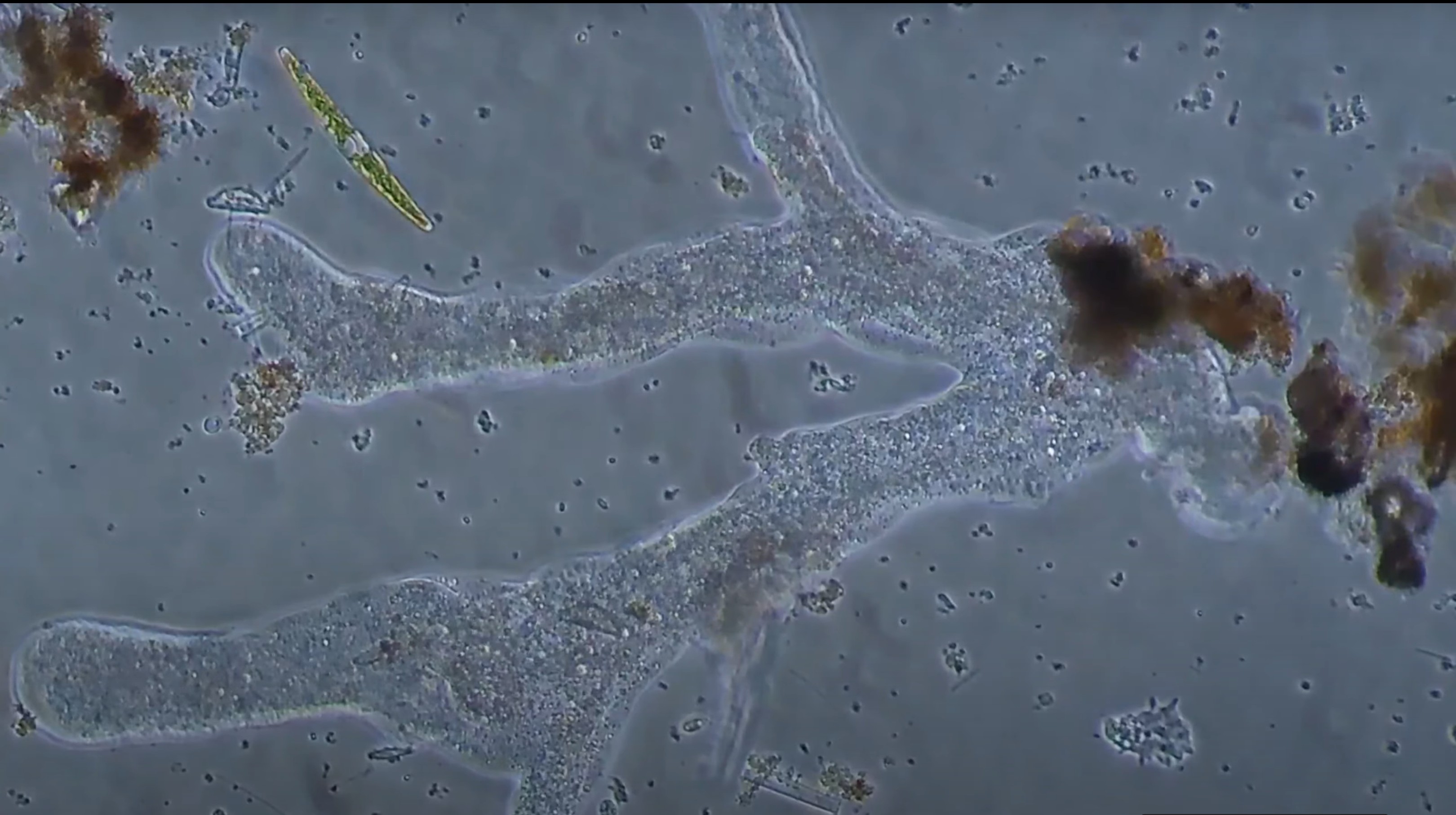

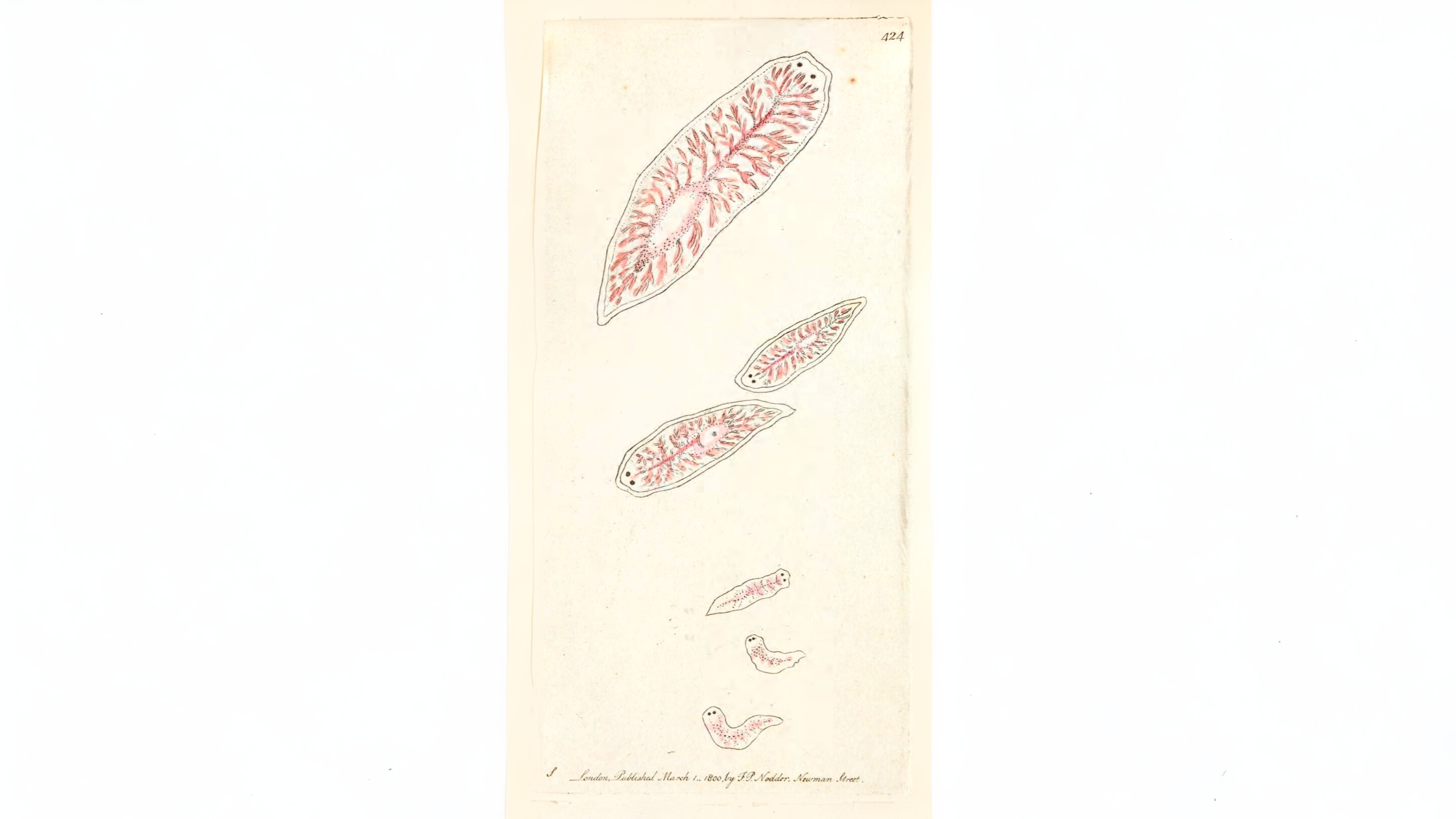

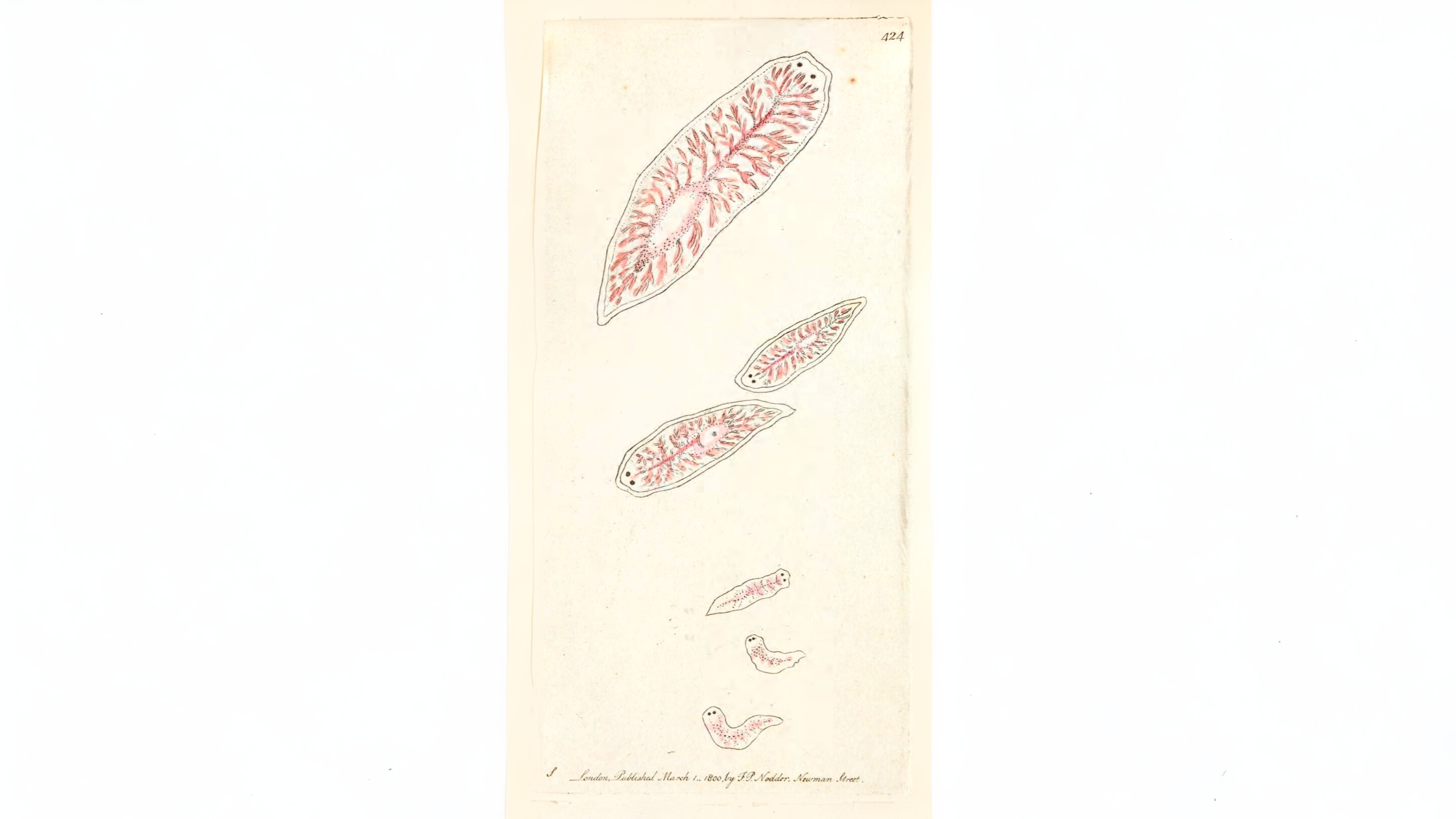

In pale species such as Dendrocaelum lacteum the patterned multi-branched gut is quite visible. This may be different colours depending on what the worm has recently eaten. Dendrocaelum lacteum is one of four different species that can be found in the ponds on Bookham Common. Flatworms are also famous for their powers of regeneration. When cut into several pieces each piece will regrow into a new worm.

Some are even known to tear themselves apart as a method of reproducing themselves. Other species such as Dugesia tigrina and D. polychroa are found under stones in London’s rivers. It is their shiny, round flattened egg discs attached to stones that are usually noticed first.