This week, London's landscapes transform into a living botany lesson. From the sapphire glow of bluebell woods to the rare marsh violet's veined petals, each flower tells a story. Did you know beggars once used buttercup sap to fake sores? Or that some violets wear tiny 'moustaches' and 'rabbit ears'?

Venture beyond parks to discover sulphur cinquefoil glowing in wastelands, ghostly lily-of-the-valley in shady thickets, and the elusive bastard balm hiding in plain sight. Even Rainham's marshes become a stage for celery-leaved buttercups performing their golden encore.

‘March winds and April showers bring forth May flowers’ – and how they do. Up until the beginning of May it is relatively easy to become acquainted with most wild flowers. From this point in the spring, the numbers of species coming into flower is sufficiently great that a short walk can result in twenty, perhaps thirty, new flowers. It may even take years to identify all you see. This is the first month nearly all of London’s habitats are worth visiting as they all have their own botanical specialities and rarities. Woods, waste areas, wet areas and downland are the richest and most varied to visit. Special wild plants associated with the month include bluebell, lily of the valley, herb Paris, water violet, sulphur cinquefoil, solomon’s seal, fritillary, early saxifrages and early orchids. Bastard balm and purple gromwell are two great wild rarities that are occasionally to be found in gardens.

This is now the time for late violets. Those most likely to be encountered are the heath dog violet Viola canina which is found on heaths and other sandy soils and the common dog violet V. riviana which prefers woods and meadows. V. canina is more blue in colour than the distinctly mauve V. riviana. If habitat and colour is not enough to separate these two, then their spur colour will. V. canina has a yellowish spur and V. riviana a cream-coloured spur. Also, V. riviana has a ‘moustache’ i.e. two sets of white hairs in the centre of the flower, whereas V. canina has none.

Although the early violets (sweet, hairy and early dog violet V. reichenbachiana) are going over, it is possible the latter is hanging on. If so, it can be confused with V. riviana as both like to line the paths in woodland. Luckily V. reichenbachiana has its famous ‘rabbit ears’ i.e. two elongated top petals and V. riviana its ‘moustache’. If this is not enough, then once again spur colour can be used. V. reichenbachiana has a dark spur and V. riviana its cream-coloured one.

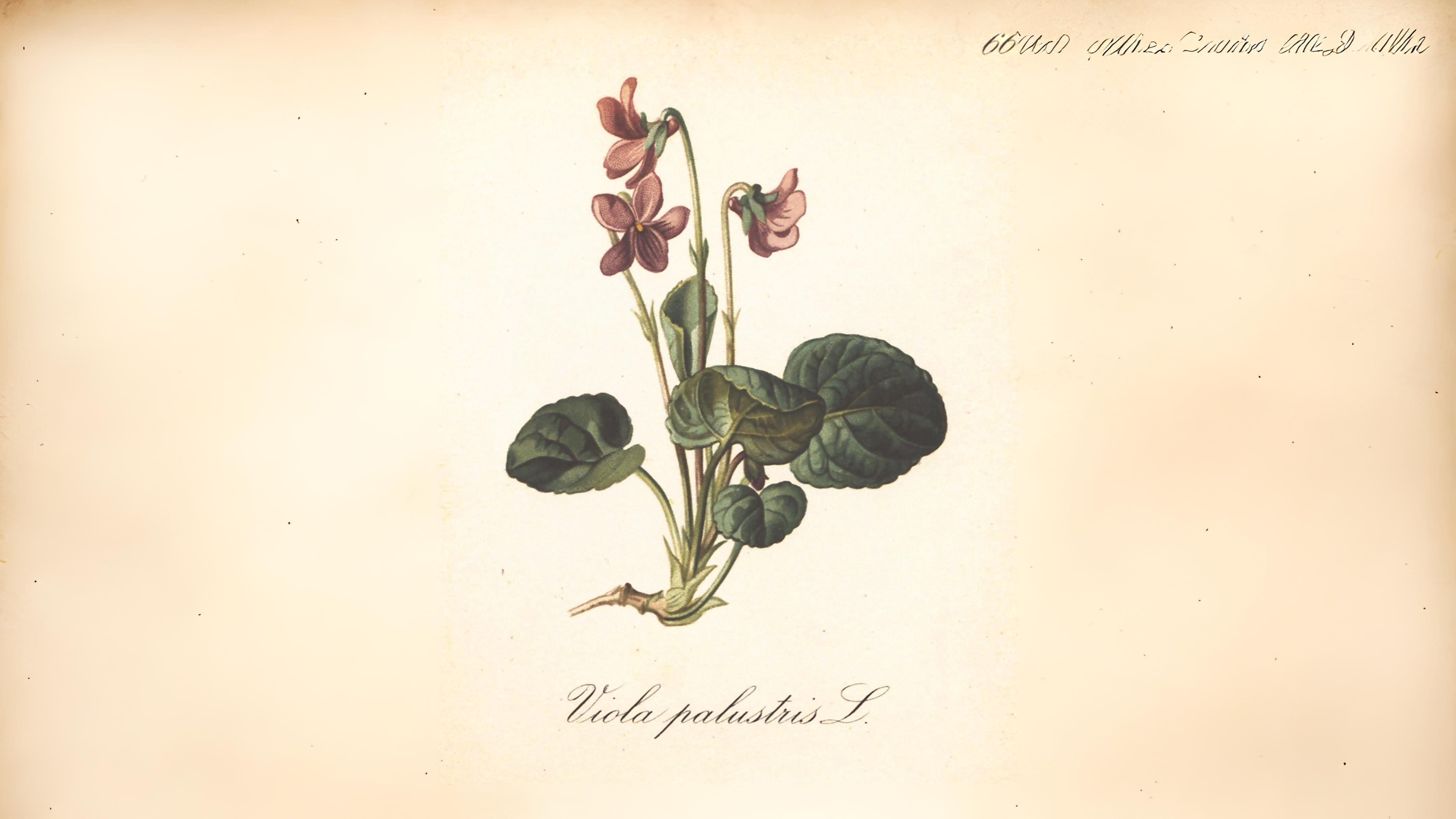

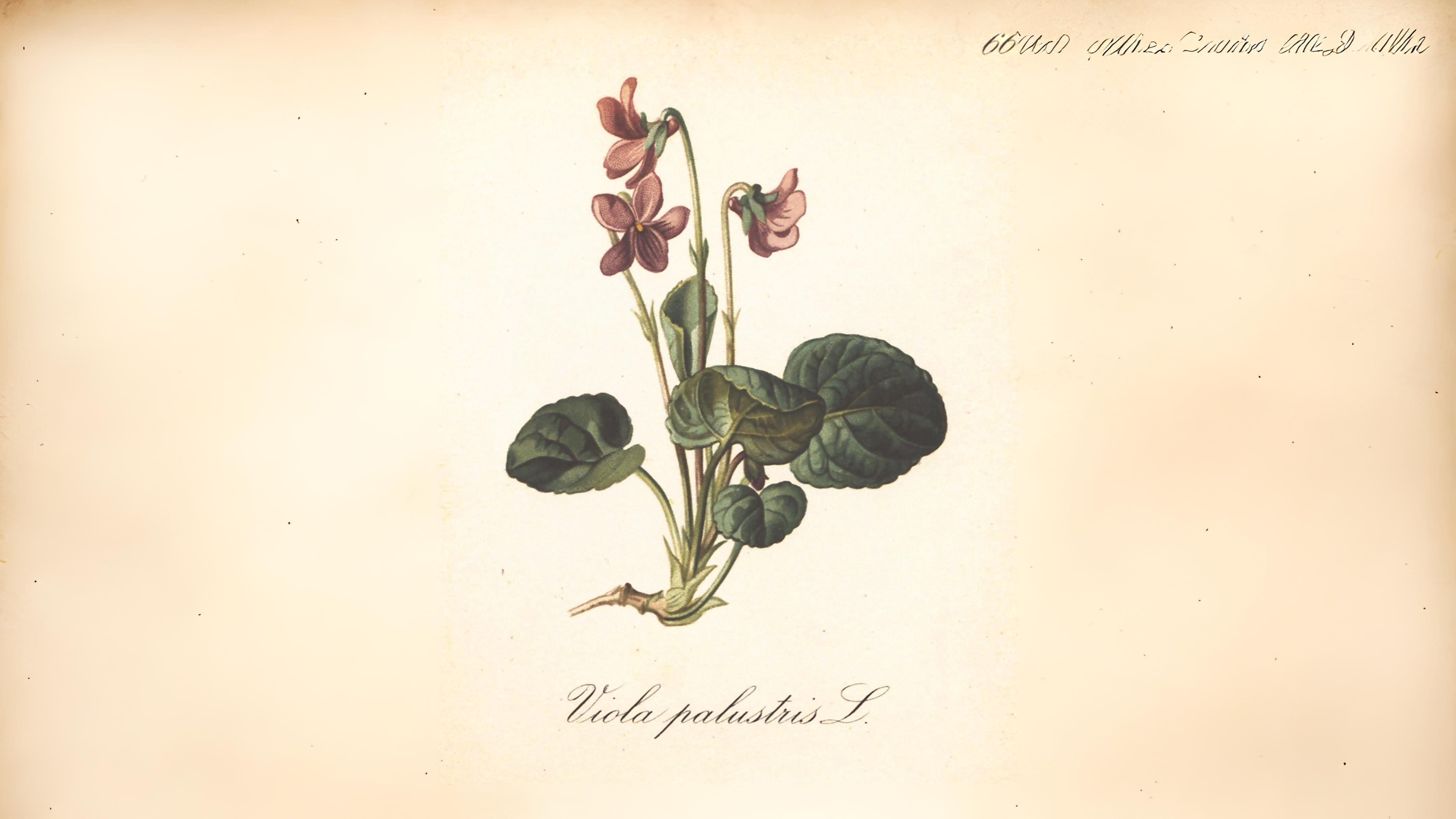

The exceptionally rare marsh violet V. palustris is also now in flower, but is nearly always confined to marshy ground. It has distinct dark purple veins on its petals and the roundest of all violet leaves, making it easier to identify than most. Black Park was one place it could be found in flower, elsewhere it often just produces leaves.

Buttercups are now appearing everywhere. The meadow buttercup Ranunculus acris is the most common in fields and pastures. Creeping buttercup R repens tends to be noticed more in gardens and parks. Goldilocks R. auricomus, which curiously often has virtually no petals, can be found in woods e.g. Three halfpenny wood. Creeping buttercup is smaller than the meadow buttercup and often identified by its runners. Goldilocks is noticeably hairless compared with other buttercups and the bulbous buttercup R. bulbosus also found in meadows, stands out due to its distinctly reflexed sepals.

Other buttercups in or near water are likely to be either the yellow-flowered marsh marigold Caltha palustris or one of the white-flowered water crowfoots R. aquatilis. Two other buttercups worth looking for are the small-flowered R. parviflorus and celery-leaved buttercup R. scleratus. These are more likely to be seen towards the end of the month. Large amounts of the latter can be seen on Rainham marshes. A much rarer, many-petalled buttercup, the globe flower Trollius europaeus and similar looking double of the meadow buttercup R. acris ‘Flore Pleno’ are only seen in gardens.

Buttercups first appeared last month, but only reach their ‘cloth of gold’ numbers in May. Their sap causes blisters on cow’s lips, which can be slow to heal. Consequently, they are ignored by livestock and go on to cover pastures. They were once called Lazarus or beggar’s weed on account of the way beggars would use their juice to promote sores on their own skin, which they found useful in extorting money when begging.